The establishment of a single European natural gas market has been the objective of the European Commission (EC) for a long time. This objective is embodied primarily in liberalisation efforts the last result of which was introduced in September 2007 in terms of the third liberalisation package proposal (1). The EC started making these efforts in the 1990’s when Europe began to perceive shortages within the existent organisation of domestic natural gas market. Among the most burning issues are the monopolistic positions of gas giants in certain areas, their oligopolistic status in the EU, the vertical integration of energy companies, long-term contracts with suppliers and the limitation of competition as well as the market entry of new players. Gas consumption in the EU has been growing. Long-range prospects don’t change anything about this fact and the dependence on external supplies from regions, which aren’t controlled by EU member states, has been growing as well (2). However, security of supply isn’t dependent solely on relations with countries where gas is extracted, but also the domestic arrangement of gas market. Right here the Union should have more influence as well as the possibility of putting own ideas into practice because it’s mainly home affairs that stand in the foreground.

The complex view of liberalisation has already been dealt with on Despite Borders pages (3). In this article, I will focus on one important precondition for the establishment of a single gas market, namely the concept of commercial places where natural gas is traded – gas hubs. They are important particularly from the point of view of gas price formation because it is the trustworthy and real price of a commodity not offered by long-term contracts, which the market needs for its existence. The price in long-term contracts is agreed on bilaterally and is bound historically to oil price development. The hubs impose the so-called “gas-to-gas competition”, i.e. the competition between gas from several suppliers. The increase in the significance of gas trading places is linked also with the growth of the volume of liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies that aren’t dependent on gas pipelines, are more flexible, stand for new gas resources from other regions and help to establish global gas market.

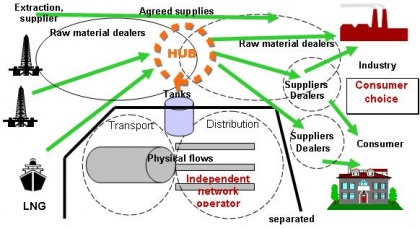

Picture No. 1.: the position of LNG supplies in future, wholly liberalised European natural gas market. It’s a view of European gas market of the future.

Source: European Federation of Energy Traders, http://www.efet.org

Since an increase in the volume of supplies as well as the importance of LNG is expected in the future, the significance of gas hubs and the relevancy of prices based on them will grow too. This opinion is confirmed by a research conducted for Flame Gas Industry in February 2007 according to which as many as 86 per cent of respondents have been awaiting such an increase in LNG importance (4).

Nevertheless, in the future gas price won’t be formed exclusively on the basis of up-to-the-minute demand and supply. Both forms of price formation, long-term contracts and hubs will coexist. It’s assumed that long-term contracts will carry on dominating in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. For instance, in the United Kingdom, 60 per cent of gas are sold for a price formed on the National Balancing Point (NBP) hub. The rest is sold in accordance with long-term contracts. As for the majority of these contracts, just their expiry is waited for.

Gas hubs at the same time represent places where alternative suppliers may show their potential on the condition that they have access to transport and distribution networks. The existent and trustworthy price is one of the preconditions for gas sector liberalisation because so far the price, or rather, the price formation has been either strictly confidential or unknown in most of the contracts.

Gas trading hubs

In general, places intended for gas trading (gas hubs) are points where gas buyers and sellers are capable of transferring the right of gas ownership to real gas possession. This definition is crucial when we take into account what kind of environment the gas is traded in and what the preconditions for the realisation of the contract itself are like. Gas trade is dependent on several factors, namely the entire infrastructure, access to networks and gas tanks and therefore it’s inflexible to some extent. Other places don’t meet these requirements for hubs.

The basic precondition for the origin of hubs is the existence and conduction of third party access (TPA) principle (5). As this precondition was carried out first of all in the US and the United Kingdom, the oldest and simultaneously the most developed commercial places are situated in these countries. By world standards, the most important hubs are the Henry Hub in the US and the NBP (National Balancing Point) in the United Kingdom

Business hubs may originate on spots where several gas pipelines encounter and from which natural gas tanks as well as consumption centres aren’t far away.

Picture No.2.: the position of hubs and natural gas dealers at the beginning of the chain, from supplies to final consumers.

If such a place is defined as a commercial one, the hub operator has to provide several services, like the interconnection of gas pipelines and a flawless transition of gas from one into another, as well as from one hub into another one; ideally, the storage tanks too. The services are important not only for seasonal gas consumption but also for flexible short-term trading. Among other things belonging to this chain are associated services and the balancing and observation of changes in gas ownership right.

The short-term balancing of gas demand and gas supply is one of the primary functions of a gas trading hub. When in proximity to consumption spots, storage tanks are an important balancing tool. Tanks themselves impart flexibility to the market.

Another factor affecting the importance of gas trading hubs is the amount of involved active dealers. It’s not possible to specify their number. However, it should be sufficient so that liquidity originates on the market and natural gas can be traded in quickly and without obstacles. Gas amounts traded by several participants must be voluminous enough so that a single transaction doesn’t influence significantly the price in gas trading hub. The aim of hubs is to obtain a positive reference that it amounts to a successful price-fixing place. This is assessed by the so-called “churn rate”, i.e. the proportion of traded gas and gas which flowed through gas trading hub. The higher the figure is, the higher the market liquidity is. In the case of US Henry Hub, this proportion was 100 to 1 in 2002, as for NBP in the same year, it amounted to 15 to 1 (this value reached 15 to 1 again in 2007) (6). In practice it says how many times the gas was traded before it really flowed through the hub.

Chart No. 1: the development of “churn rate” in the British hub NBP.

Source: European Trading Developments, Heren, http://www.heren.com

The hubs themselves are divided into two types: virtual ones and physical ones. Among virtual gas trading hubs is, for example, the British NBP, which covers the whole transport system of the company National Grid Gas plc (7) (for the sake of better understanding – NBP is the complete transport network of gas pipelines in the territory of the United Kingdom). British system represents a network and it developed into this shape owing to short transport distances and the number of inputs and outputs within the system. As soon as gas enters this network, it’s regarded as a gas which entered the gas trading hub. Gas input and output are charged. Thus it’s the classic entry/exit system. The proportion of spot (short-term) contracts has been stepped up thanks to the functioning hubs.

An instance of a physical gas trading hub, which various gas pipelines run into or cross and which is connected directly to storage tanks, is Henry Hub in the US or Baumgarten in Austria. Henry Hub is the biggest commercial gas hub in the world. It developed historically into this position. In the US, open network access was imposed as early as 1986 (8). It’s situated in southern Louisiana, it connects twelve gas pipelines and there are three storage tanks in its proximity. It’s the most liquid hub in the world and it serves as a reference point for futures contracts trading on the New York stock exchange (NYMEX) (9).

When the hub evolves into a liquid commercial place, operations, like spot and futures markets, start to develop and together with them the market price for current and future commodity supplies will appear. (Spot) trading begins with simple OTC (over-the-counter) trading which represent bilateral agreements between a seller and a buyer or via a broker. Among other possibilities are futures markets which stand for independent and transparent price signals for following price development of the commodity. Thus they serve as the indicator of other contracts. It means that future price represents the up-to-date market view of the question how much the gas will cost at any given time. According to these data the gas is either put into the tanks or sold. Active hub trading is reflected in the development of price, which isn’t as stable as in the case of long-term contract. That’s why daily price deviations and daily trading are limited. It is the daily deviations which are one of the greatest objections against gas trading on the supply-and-demand basis. This objection is logical, but its origin is more of psychological character. In the case of hub trading, final consumers won’t have the gas price changed every day. The prices will be averaged out and therefore the consumers won’t perceive if price deviations are high or low during the day. Besides this, gas is invoiced at longer time intervals, which contributes to the restriction of high deviations. Electricity price, for example, is much more unstable because in contrast to gas this commodity isn’t to be stored and it has to be consumed.

Chart No. 2.: the comparison between oil indexed gas prices and prices formed by NBP hub (annual average).

Source: Development of Competitive Gas Trading in Continental Europe, IEA, May 2008, page 44

The problem is that investments in power engineering are one of the most capital intensive ones and therefore investors need price guarantees that market trading doesn’t offer to a sufficient degree. Anyway, response to these objections is the condition that hub trading must be fair and efficient. A hub is capable of sending high-quality market signals on the condition that it’s liquid and the price formation is transparent. The signals themselves inform about necessary investments in infrastructure so that this can develop in accordance with natural gas market requirements. Price instability is improbable on a market with an excess of gas, however, it poses a threat for a market which is tense (10).

The first natural gas futures contract on the NYMEX stock exchange was concluded in 1990 and its reference point was Henry Hub. In the United Kingdom, first such a contract was concluded in 1997 and its reference point was the NBP hub. It’s clear that trading in gas as a commodity is only at the beginning. Meanwhile, it’s aimed at the most advanced markets. Characteristic of this market is a thorough application of third party access – TPA, the real imposition of which (not just the declared one) is pursued by the EU. Nonetheless, it’s to be mentioned that in the period when the US and the UK started to apply this principle, both countries weren’t dependent on gas supplies from other countries, but they had own raw materials that covered their consumption. Continental Europe is in a different situation. It covers most of its gas consumption through imports from external sources. Moreover, we cannot forget about considerable European dependence on solely three significant suppliers (Norway, Russia and Algeria).

It is the TPA principle which enables the consumers to choose their own raw material supplier. The stepping up of supply results in the modification of offered service. Nowadays, classic suppliers offer all-in-one service, i.e. the consumer pays also for services which he doesn’t need. The choice from among several possibilities creates room for paying just for the service which the consumer picks. The Dutch company Gasunie was the first in continental Europe to offer the possibility of choice. Among the services that it offers are peak capacity, seasonal deviations and temperature-related backup (storage in the case of a striking temperature increase and simultaneously gas consumption growth or in the case of an opposite situation, i.e. if the temperature is higher than expected and gas consumption has sunk). At present, similar services have become commonplace. Not all consumers, however, are authorised to enter similar contractual relations and the criteria are defined mainly by the volume of natural gas consumption. Thus the consumer accepts a risk in a new form, i.e. in terms of the contract it doesn’t include guaranteed supply under any circumstances, but it picks those circumstances which are the most important ones for it. Moreover, consequences emerging from the selection of an unsuitable service are linked with it as well.

Under these conditions the question arises how to ensure stable supplies for consumers which aren’t able to remain without gas, which haven’t got the possibility of switching the energy source for a short time and whose demand is dependent on external temperature.

Along with gas trade in terms of gas trading hubs also commodity tanks, the importance of which grows perpetually, have been developing. In individual countries, they have been administered by independent companies, although from the historical point of view, they were the property of local distribution companies. Storage tanks are to be used in the case of price deviations. The company buys cheaper gas and sells it at a suitable time for a higher sum. Undiscriminating access to networks is a prerequisite. However, their primary original purpose, which is the most crucial today, is the balancing of seasonal consumption deviations. The task of tanks has grown also in the field of security of supply in the case of physical transport interruption or in the aftermath of geopolitical tensions. Gas supplies in tanks are situated in places close to gas trading hubs. In contrast to previous times, they are traded continually and thus altered more often than only once a year. Besides physical storage tanks there are also virtual storage tanks. These are a part of services provided by the companies. Virtual capacity, however, must be ensured by existent physical free capacities. It exists just in regions with sufficient exchange of natural gas and its flexible trading. In terms of the EU, access to tanks is the most advanced in the United Kingdom where free capacities are sold on auctions and the virtual room is bought on spot markets.

Since natural gas is to a large extent utilized in electricity production and electricity is a commercial commodity, there’s a correlation between the spot prices of natural gas and electricity.

Graph No 1.: the proportion of natural gas in electricity production in some EU countries.

Source: Kingston Energy, http://www.kingstonenergy.com/eugas0308.pdf

As long as electricity price is higher than gas price in a power plant, including production costs, its production continues. However, if gas price, as the price of an input commodity, soars above the level of electricity price, which thus becomes financially less interesting, electricity producer can keep on selling gas instead of producing it and buy electricity on the market. This happens only if further natural gas sale is permitted by the supply contract (11). This is mostly allowed in hub trading. In such a case, electricity spot price influences directly natural gas spot price. After some time, the situation alters owing to market forces and gas turns into an efficient source of electricity production again.

The summary of the most important European natural gas trading hubs

NBP – National Balancing Point. This British virtual hub, which has been already mentioned several times, is the most developed gas trading gas hub after Henry Hub (12). The precondition for its origin were the closeness to gas extraction in the North Sea, the existence of several transport network input/output spots (five in total) and relatively short distances within gas transit. The capacity of input/output spots is offered at regular auctions and divided into long-term capacity and short-term one. On a secondary market, participants may trade in acquired capacity among each other. It’s the auctions which are generally considered a transparent way of capacity sale. They also offer price if there’s a lack of capacity for instance.

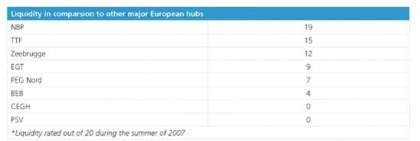

Apart from gas from the North Sea, the British system is attached to several other sources as well – gas imported from Belgium via the gas pipeline Interconnector, the LNG terminal Isle of Grain as well as gas from the Netherlands through the BBL line (Balgzand-Bacton Line). According to all measurements (the volume of traded gas, churn ratio) it’s the most liquid hub in Europe, which is proved also by the following chart.

Chart No 3.: the liquidity of hubs (the maximum amounts to 20 points).

Source: Heren, Development of European Gas Trading, http:/http://www.cessa.eu.com/sd_papers/cambridge/CeSSA_Cambridge_301_Allpress.pdf

In 2007, the churn ration accounted for 15 and equalised thus the best period in 2002. Other hubs in Europe are considerably smaller in contrast to the NBP, which is apparent in the following chart.

Chart No.4.: the traded volumes.

Source: European Trading Developments, Heren, http://www.heren.com

Zeebrugge Hub. The Belgian hub established in 1999 ranks among the most important gas trading hubs in the territory of continental Europe. Its interconnections stretch from the connection with the United Kingdom, through the connection with Norwegian offshore fields in the North Sea to transit gas pipelines leading to France, Germany and the Netherlands. It’s linked with an LNG terminal too. From this point of view, this physical hub is a more interesting, or even ideal, place for trading and meets the fundamental criteria of transparent price formation.

Among the main limiting factors of the hub are the difficulties with gas transfer due east from Zeebrugge. The cause is the historical inclusion of primary high-pressure gas pipelines in Germany, France and the Netherlands in “transit” ones. Thus they don’t come under the third party access (TPA) principle. Today, the capacity of these gas pipelines is determined by long-term contracts, which hampers the development of a more competitive market in the region (13). On the one hand Zeebrugge is one of the most liquid continental commercial hubs, but on the other hand it’s restricted by inadequate interconnections with markets. Thanks to the connection with the United Kingdom via the gas pipeline Interconnector, spot market arbitrages between NBP and Zeebrugge are conducted. As the continental hub is less developed than the British one, its gas price copies the price fixed on the British Isles.

Nevertheless, there has been a liquidity stagnation of this commercial hub recently. Among other negative factors are issues with varying gas quality, the primary position of the transit hub and input capacity controlled by domestic monopoly companies

CEGH – Central European Gas Hub: The easternmost hub in Europe situated in Austrian territory in Baumgarten near to Slovak borders is the most crucial one for Slovakia. It belongs to younger gas trading hubs. Its origin is directly linked with the expanding liberalisation of energy sector in the EU. In the period when the possibility of placing a hub in Central Europe was being decided on, among the options was also the Slovak village of Láb (14), the geographic conditions of which were similar to that ones in Baumgarten.

Baumgarten lies at the junction of two gas pipelines, namely Bratstvo and Transgas. The difference between the Austrian hub and other European ones is that all gas in Baumgarten comes exclusively from the Russian Federation. Since Gazprom has a monopoly on gas exports from Russia, it’s the only gas supplier to this hub. This fact was behind the Russian company’s interest in entering CEGH. Gazprom succeeded in entering it January 2008. That time, an agreement between OMV Gas International (the holder of the 100 per cent share originally) and Gazprom on company entry and the acquisition of a 50 per cent share in commercial platform was signed. The goal of this gas trading hub is the creation of one of the most liquid platforms in Europe.

The advantages of the hub are a great deal of destinations which take gas flowing through Baumgarten. This makes it a point with business potential. The main gas destination is Italy.

Recently, the volume of transport through Baumgarten has been growing, but the liquidity has been stagnating. Such a development contributes to the dominant position of Gazprom as the primary supplier.

CEHG development and Slovakia

Gas source is the most limiting factor of the development of the Austrian hub. It is the broader portfolio of suppliers which is one of the signs of a successfully developing commercial place.

In this context, there are several projects which will carry a larger volume of gas from new destinations into the EU. On one level it is the gas pipelines Nabucco and South Stream. On another level it is the LNG terminal in Croatia Adria LNG. Whereas South Stream wouldn’t extend the number of gas suppliers, as it is a Russian project, Nabucco would manage to transport gas from Azerbaijan and potentially from Iran and Central Asia. However, there is more politics than rational economic deliberation involved in matters concerning both pipes and it remains a question which route will be built in the end. Anyway, both are supposed to end in Baumgarten.

Along with the growth of oil prices, LNG supplies have been gradually becoming more and more financially competitive. The demand for this kind of raw material has been increasing, which is connected with gradual establishment of world gas market according to the oil market pattern. The competitiveness of LNG is directly proportional to the distance which gas is imported from. The boundary distance amounts to 3,700 km. Beyond this distance, the LNG transport costs are lower than the transport via the continental gas pipeline (13).

Two gas terminals are planned in the vicinity of Central Europe. One of them is supposed to be in Croatia on the coast of the Adriatic Sea on the island Krk and the other one in Poland. Meanwhile, Adria LNG is a more real project. It would be able to supply gas to surrounding countries, i.e. Italy, Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, Romania and Austria. The disadvantage of LNG supplies is that it’s necessary to construct the missing infrastructure or to open up at least the existent gas pipelines in both directions. In this way gas from Adria LNG could reach even Baumgarten. In combination with supplies via Nabucco or South Stream, a higher liquidity of the hub would be achieved. The presence of storage capacities in the surroundings is a positive factor too. They are not only in Baumgarten, but also in Slovak Láb. Further construction of capacities in Hungary was considered as well. Their realisation in this country was the subject matter of last year’s negotiations about the support of the lengthening of Blue Stream among Gazprom, Hungary and Austria. That time, Gazprom was promising concurrently both sides to reinforce the position of the gas hub in Central Europe. Proposals to build further tanks were related with this. In the end, however, Gazprom entered CEHG and the issue of Hungarian hub became out-of-date. It remains a question what the impact on the plans for tank construction in this country will be like.

The Slovak tanks Láb IV, which are administered by the company Nafta joint-stock company, are presently connected with Baumgarten. The hub is also attached to Slovak gas system through gas pipelines DN 800, DN 600, DN 500, DN 900 a DN 1000 and it’s necessary to extend the interconnection in the future. According to the Energy Security Strategy it’s technically feasible to import gas across western borders from Austria and the Czech Republic nowadays (14).

It is the existence of Baumgarten hub as well as the not fully exploited capacities of the gas pipeline in Slovak territory which stand for a possibility for alternative natural gas suppliers in Slovakia. However, the imposition of undiscriminating third party access to transport and distribution networks is a prerequisite. These conditions would create room for market penetration not only for such gas suppliers which have above-standard relations with Gazprom, are its daughter company or have non-transparent financial background, but also for those already established in other countries. The problem is that nobody knows how they will get on in Central European conditions where Gazprom has almost a monopoly.

Gas price in the hub is also questionable. Since the Slovak Republic still hasn’t concluded a contract with Gazexport on gas supplies for the next period yet and the representatives of Gazprom have already announced price growth in Europe, it’s highly probable that both ways of gas acquisition will still more compete with one another.

The attachment and access to transport and distributions network is overseen by the Regulatory Office for Network Industries because access represents a regulated activity (15). The basis of the establishment of competitive environment in the Slovak Republic is formed right by the strong position of the regulator as well as the independence and acceptance of its decisions. The regulator is obliged to create and oversee the abidance by stimulating conditions for new market subjects. Under contemporary conditions, however, the Office hasn’t got enough experts that would be able to communicate with the SPP equally.

The development of the hub in Austria would affect positively also the entrepreneurial activities of Nafta joint-stock company in Láb, which could profit from favourable position and existent interconnection. Slovakia should be interested in the strengthening of own interconnections with surrounding countries, Poland in particular. Thus our territory might serve as a transit point not only for Russian gas supplied in accordance with long-term contracts.

The draft proposal of energy security strategy, which is a framework document for energy security, doesn’t deal with the utilisation of Baumgarten’s vicinity. Nevertheless, the Slovak Republic is interested in further development of the commercial hub and the acquisition of other possible gas sources. It means the support of the pipeline Nabucco and the terminal Adria LNG and the quest for direct participation of the Slovak Republic in these projects. By means of the country’s share in SPP, this strategy could be influenced and put into practice. Furthermore, it’s crucial to uphold the cross-border interconnection and the opening up of markets to sustainable competition. Such a development would have positive impact predominantly on natural gas consumers. These would be allowed to choose their own supplier and pay only for the service agreed on in contracts. So far the stance of Slovak state bodies, however, has been in contrast to gas liberalisation introduced by the European Commission. Also state policy gives preference rather to the consolidation of the positions of established companies.

It is the analysis of all conceivable alternatives to supplying the country with gas and the real opening of market to new players which amount to a challenge for responsible bodies and offices. These steps form a mosaic at the end of which we will see whose interests are preferred: those of final consumers or those of established energy companies. The effort to impose principles in terms of competition growth in energy sector is sure to be more conducive than media statements about the regulation of gas and heat prices for consumers.

Notes:

20European%20gas%20demand.pdf; European Energy Security: An Overview of Natural Gas Demand, Production and Imports to 2030. International Association for Energy Economics, http://www.iaee08ist.org/DownloadAbstract.php?PI=121&T=2(3) Ševce, P.: Liberalizácia vnútorného energetického trhu v EÚ, February 2008,

/clanky/data/upimages/sevce_liberalizacia_energetika-EN.pdf(2) Cross Border Trading in Europe. 2007 FLAME Gas Industry Survey Results, February 2007, http://www.energyblogsite.com/download.asp?File=/ia/pdf07/

crossbordertradingeur.pdf

(3) Infrastructure and Trading in a Common European Gas Market. The Trader’s vision, European Federation of Energy Traders, May 2004, http://www.efet.org/Download.asp?File=993

(4) Powell, W.: Gas liberalization in Europe. An empty promise? In: Global Energy Business, January/February 2002, s. 30 http://www.analyticalq.com/published/gasliberalisation.pdf

(5) National Grid Gas plc is British gas operator.

(6) Natural Gas Market Liberalisation: A New Context For Flexibility. IEA, Sylvie Cornot-Gandolphe,2002, s. 20

(7) http://www.oilnergy.com/1gnymex.htm

(8) Natural Gas Market Liberalisation: A New Context For Flexibility. IEA, Sylvie Cornot-Gandolphe,2002, s. 29

(9) „Towards a true EU gas market.” Fundamentals of the World Gas Industry, 2008. http://www.kingstonenergy.com/eugas0308.pdf

(10) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Balancing_Point_(UK)

(11) Development of Competitive Gas Trading in Continental Europe. IEA, May 2008, p. 48, http://www.iea.org/Textbase/Papers/2008/gas_trading.pdf

(12) Natural Gas Market Liberalisation: A New Context For Flexibility. IEA, Sylvie Cornot-Gandolphe,2002, s. 24

(13) Klepáč, J.: Je skvapalnený zemný plyn perspektívny pre krajiny strednej Európy? Slovgas, č. 3, 2008, s. 10

(14) Návrh stratégie energetickej bezpečnosti. Bratislava, Ministerstvo hospodárstva SR, http://www.economy.gov.sk/index/go.php?id=3167

(15) Hvizdoš, L.: Regulácia prirodzených monopolov v krajinách V4. Slovgas, č. 3, 2008, s. 15